Disinformation, misinformation, malinformation and fake news: Cracking the code of information disorders by Gracia Sumariva Reyes

Echoing through online discussions and media headlines, terms such as ‘’information manipulation’’, ’disinformation’’ and ’fake news’’ have become commonplace. Yet, as these buzzwords become trendier, do we really know what they mean?

The word information derives from the Latin informare which means ‘to instruct, teach or shape the mind’. Every day, we are exposed to tons of messages that end up impacting the way we think and see the world. Sometimes in a positive way. Sometimes in a negative way.

Traditionally, journalists and the media have been the social actors tasked with meeting the population’s demand for information. According to the gatekeeping theory, they are in charge of filtering the information and elaborating the messages, such as news, that will reach the public every day. These messages, theoretically, should be constructed under an ethical framework, which puts at the centre the citizen, society and its rights. As a result, the media seek to disseminate quality information: in the public interest, produced in good faith and as objective as possible.

The rise of new communication technologies, especially the Internet and social networks, however, has brought about major changes in the ways information is produced and distributed. Internet’s low costs and entry requirements make it possible for anyone to be able to disseminate information. This information, which often goes viral, tends not to adhere to media standards of quality and veracity and can suffer from some form of ‘information disorder’, such as disinformation, misinformation or malinformation.

Types of information disorders

The Council of Europe in its report ‘Information disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making’ (2017) identifies three types of information disorders: disinformation, misinformation, and malinformation. While these terms all relate to the spread of inaccurate and misleading information, they each exhibit unique characteristics which must be acknowledged and taken into consideration when crafting effective responses to combat the challenges posed by them.

Disinformation

Disinformation occurs when a piece of false information is deliberately fabricated and disseminated with the purpose of wreaking havoc against a person, institution or country. It often pursues political or economic purposes, such as influencing public opinion, manipulating political events or achieving financial gains.

An example of a recent disinformation in Poland, detected and debunked by Demagog, is a publication spread on Facebook by the group NIE dla szczepień (NO to vaccination) which linked herd immunity of vaccination programs with that sought by the Nazis during the Third Reich. This connection is totally misleading and false. Claims of herd immunity made by authorities are based on legitimate public health strategies involving vaccinations, while claims made by the Nazis were unrelated and should not be equated as they involved inhuman crimes and atrocities. The spread of disinformation narratives like these seek to delegitimise vaccination programmes as well as health authorities and the Government. Furthermore, this example highlights how disinformation is not only spread in texts, but also through other formats such as images and memes.

Misinformation

Misinformation is like the twin brother of disinformation: they look very similar but have a difference. Both include the diffusion of information that is not based on factual reality. However, in the case of misinformation, this action is non-intentional but rather due to poor verification and fact-checking. Rumours that people share in the face of breaking news that have not been verified to be true are good examples of misinformation. According to a study on fact-checking habits carried out by the University of Ohio, most people do not verify whether a new piece of information is accurate or fake before sharing it on social media. On many occasions, trying to be helpful, users fail to adequately inspect the information they are sharing. News verification, as easy as googleing and not sharing it right away, is a very helpful action, especially in contexts of high information saturation such as the current conflict in Ukraine or the tragic events in the Middle East.

Malinformation

Malinformation is information that although based on reality, is disseminated with the purpose of causing harm to a person, a group, an organisation or a country. Generally, it refers to the strategic use of real information, including leak of classified information, to cause harm.

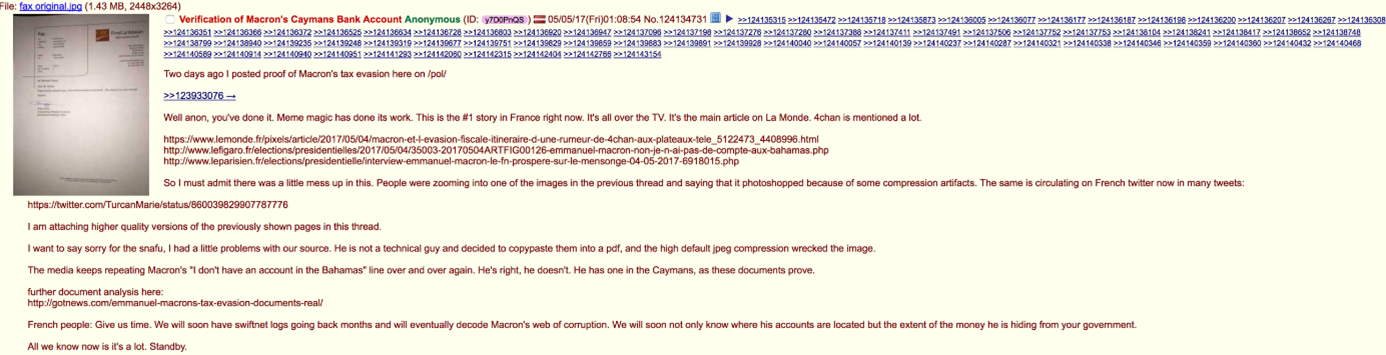

One of the most famous examples of malinformation is the #MacronLeaks campaign. In the run-up to the 2017 French elections, there was a coordinated attempt to undermine Emmanuel Macron, with a leak of more than 20,000 emails, published on Friday 5 May 2017 – just two days before the second and final round of the presidential election. This leak was initiated in alternative social media platforms and after promoted on Twitter by an army of trolls and fake accounts (bots) under the hashtag #MacronLeaks. To the dismay of the Kremlin-linked malign actors, democracy won and the Macron Leaks operation did not influence French voters or change the outcome. With 66.1 percent of the vote, Macron defeated his far-right rival Marine Le Pen.

Screenshot of one of the posts on 4Chain where various documents were leaked. This documents were framed in a narrative that sought to undermine Macron’s reputation. Moreover, not all the sensitive documents leaked were real. Below, we see a psychedelic email, supposedly written by the general director of affairs of En Marche (currently, Renaissance), Macron’s party.

And the omnipresent fake news?

The term fake news is used to refer to messages that suffer from one of these information disorders. However, the Council of Europe advises against its use because of its lack of precision and its weaponisation by politicians to refer to information that does not align with them. A more acceptable term in this sense is that of ‘false news’, proposed by Facebook, to refer to news articles that purport to be factual, but contain intentional misstatements of fact to arouse passions, attract viewership or deceive.

Conclusion

According to Eurostat data for 2021, 72% of Internet users in the EU aged 16-74 read online news sites, newspapers or news magazines, an increase of 2 percentage points (pp) compared to 2016. In this context, users prefer to get information from social networks rather than direct access (28% vs. 23%), as claimed by Digital News Report 2022 from the Reuters Institute. However, these environments are especially susceptible to the circulation of sick information, like disinformation, misinformation and malinformation. So, what is the best solution? Awareness, hunting down manipulated information and, above all, verification, verification and verification.